Severity

from Friday, May20th of the year2011.

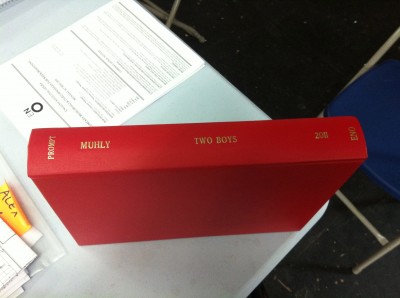

So, our first week of putting together Two Boys in London is over, sort of, and the whole thing has been surreal and wonderful. I’m still unaccustomed to the number of people working behind the scenes on a production like this: there are a few dozen in the rehearsal room and then another few dozen back at headquarters all basically putting together a piece of music I started sketching on a Delta Shuttle tray table three years ago. It’s weird to go from that to this:

or, stranger yet, to go from a little scribble that says “chorus enters?” to:

It’s very moving! And that’s just a third of them! I am trying to be avuncular rather than mommie dearest with this project, so I’m coming in for a bit of the day and spending the rest of the time hiding out. I have observed something about singers which I would love to have some feedback about: they seem really freaked out about making mistakes in front of “the composer.” I don’t know many musicians who feel this way; in fact, most people I know — and I include myself in this — prefer to present the composer a semi-molded thing, warts and all, that then, with collaboration, becomes something more polished. Singers seem to want to take it a little bit farther, and definitely under no circumstances want to sight-read in front of the composer. Any thoughts on this?

Last night, I went to the opening night of the ENO’s new production of Britten A Midsummer Night’s Dream. You guys, I loved it so much. I love this opera anyway (read my somewhat complicated discourse about it from a few years ago, which, if you can bear my screed at the top, yields some lovely performance practice examples at the bottom) but this production was something very severe, rigorous, and special. The director, Christopher Alden, has imposed (or, rather, teased out) an additional narrative from the opera (which itself is a simplification of Shakespeare’s original). This additional narrative is, essentially, that Oberon is a paedophile schoolmaster, and that Puck, who had once been his favorite, is being eclipsed by the Indian Boy/Changeling. The staging makes a few things very explicit and allows other things to be registrally hidden; in one moment, Puck is essentially trying to regain Oberon’s affections in a twisted, 14 year-old way that’s simultaneously ragingly emotional, sexual, and very sad. It’s a failed embrace met with absolute coldness by Oberon’s unforgiving countertenor, and I found myself chilled and incredibly moved. An additional layer implies that Theseus himself — who observes the entire opera, loosely, grimacing and making assorted moues as he watches Puck — was himself subject to this same attention from Oberon in the past. The programme the ENO provides makes this more explicit, quoting at great length this article from 2001 (without counting words, it seems like they quoted about 95% of it, leaving out a few choice tidbits like, “I hated the taste of his semen,” which I suppose is for the best, but I do enjoy the image of a dutiful ENO employee expurgating the original article with a razor blade and a loupe or something), as well as a slightly more nuanced article by John Bridcut, whose 2006 book Britten’s Children is a fabulous (and just the right length) exploration of Benjamin Britten’s own relationships with teenage boys from when he was himself one through his death.

The reviews have been exactly as you might imagine, and my conversations with people about it have been absolutely as you might imagine; there is a kind of great review of it that I basically agree with entirely except for the point of it, which I suppose I almost, to a certain extent share; a beautiful moment happens when we realize that Theseus is, in a sense, grown-up Puck, and that before he marries Hippolyta he has to confront his having been passed-over by Oberon; this is something with huge resonances in Britten’s Children and I think everybody should just go buy it and read it right now anyway. The other point this review brings up is the severity of the production to completely deny us the restorative and playful benediction of the ending. May I confess that I have always found the last few bars of Midsummer to be a little bit “That’s all, folks?” This production went against the grain of the text(s), but lord hammercy, to hear this angry boy read these lines:

If we shadows have offended,

Think but this and all is mended,

That you have but slumber’d here

While these visions did appear.

[…]

So, good night unto you all.

Give me your hands, if we be friends,

And Robin shall restore amends.

…after all the innuendo, cardigan brokebacking, and that heartstoppingly amazing final chorus with the boys and the countertenor and Tytania’s toe-curling descant, I kind of didn’t mind how off it was, or at least different from the nine thousand versions we’ve seen of it before. Insert aside here about authorial intent…but really, there is a home in the world for “traditional” readings of this work (both the Shakespeare and the Britten, and I own, have seen, and will see many, many more of them), and this production doesn’t imply that its reading is the correct one; it’s just a beautiful, moving, severe interpretation. It’s been a long time since an opera has arrested me in that way, and I’d like to think that when I’m dead, somebody could use something of mine to make a similarly powerful gesture.

Another kind of funny aside was that one good friend, whom I will not name because I adore him, began his litany of complains against the production with the fact that it had started in two minutes of silence as Theseus prowled across the stage. Something that I find especially strange about the English opera world — and let it be said that I actually know nothing about this, this is more of a general impression from my limited experience — is that even the smallest, like, Tesco-wrapped, overly-curated galangal root of European, regie-ass production is still too spicy for some of these people. Straight theater-goers (and fans of new music) in London seem way ahead of the curve, where it’s like, Sarah Kane 4.48 Psychosis every two seconds and Black Wartch and really kind of outrageous Shakespeare productions and all the Gerald Barry you can shake a scepter at but then two minutes of silence at the head of the opera is offensive? The point is, it seemed odd that a little silence with a prowling Theseus ruffled the feathers; I hesitated to tell my friend that I, in college, provided incidental music for a production of the Shakespeare Midsummer in which all of the court’s proceedings were conducted in Medieval Korean, the faeries were suspended in sex slings the entire time, and the audience was gender-segregated into groomsmen and bridesmaids (and do not think for a moment that this reinforcement of the gender binary was not mise en evidence by several theatergoers).

The other great thing about last night was Sir Willard White, holy shit. He was so amazing as Bottom, I was losing my mind. During his transformation, he removes his shirt, which is technically fascinating because we got to watch exactly how it is that he controls his diaphragm. It’s something extraordinary; the flesh is suspended over the muscles in a very revealing way. I’d urge any singers out there to do more work shirtless, or videotape yourselves and get involved. It was like watching a Mark Morris rehearsal on his abs. Also does everybody remember how great Willard White is in El Niño? There’s a little three-minute nugget in the first part that I steal every two seconds; this business with the low low piccolo is really perfect at doing stillness with potential energy.

The other great thing about last night was Sir Willard White, holy shit. He was so amazing as Bottom, I was losing my mind. During his transformation, he removes his shirt, which is technically fascinating because we got to watch exactly how it is that he controls his diaphragm. It’s something extraordinary; the flesh is suspended over the muscles in a very revealing way. I’d urge any singers out there to do more work shirtless, or videotape yourselves and get involved. It was like watching a Mark Morris rehearsal on his abs. Also does everybody remember how great Willard White is in El Niño? There’s a little three-minute nugget in the first part that I steal every two seconds; this business with the low low piccolo is really perfect at doing stillness with potential energy.

[audio:SeHableDe.mp3]

John Adams El Niño

Se Habla de Gabriel

WW starts a minute or so in. Listen to how good those string drones are!

9 Comments

May 20th, 2011 at 5:17 pm

Regarding your observation about singers in front of composers – this past week I had my first equity reading of a twenty-minute musical I wrote at Tisch. My collaborator and I were in the room the whole time, even as the singers were learning the music for the first time. For the most part, they seemed comfortable stumbling through and messing up the music early on. Everyone once in awhile you’d encounter an actor who would repeat, “I promise I’ll have it by tomorrow,” over and over, but it seemed like most of them were comfortable sight-singing and learning in front of the writers.

“Surreal and wonderful” is definitely the right way to express seeing your work come to life. Congrats on your first week of Two Boys!

May 20th, 2011 at 5:51 pm

Nico,

To try to answer your question regarding singers being nervous when performing in the presence of the composer (assuming we are talking about a composer who is still alive, otherwise the quaking would be entirely justified for anyone), could it be that for singers, unlike other musicians, their musical production is totally unmediated – they are naked and can’t hide behind an instrument. Totally vulnerable! And then that guy who knows the piece inside out since he wrote it is right there, clearly hearing every fault and weakness IN THEIR VOICE . . .

Singers, and actors, can be like very delicate tropical plants in a temperate environment: they need a lot of protection so they do not wither because of some cold draft, real . . . or imagined!

P.S. I am not a singer, but a theatre director.

May 23rd, 2011 at 11:13 am

Nico,

I think you’re right on in terms of the collaboration. I try to make clear that we’re all working together to make the piece better. I’ve noticed that if the singers also come to rehearsal with the same collaborative ideal, everybody can learned from mistakes.

Hope all goes well in London! Toi toi toi!

fp

May 24th, 2011 at 11:17 pm

I love it when you write about Britten, Nico – actually, the first thing I ever read by you was your Peter Grimes piece for the Met, and that was why I checked out your music. You should write a book on Britten, you know, or at least do a collection of pieces about various composers/works with a major section on Britten.

May 25th, 2011 at 10:05 pm

Williard White, in my limited experience of hearing him in “Khovanschina” and “El Nino” and “Saint Francoise d’Assisse”, is pretty much god. I’ve never understood why he wasn’t a bigger, more acknowledged opera star.

May 30th, 2011 at 7:43 am

you are amazing. thanks, as always for sharing your insights into the process and your wonderment with the world. And, as a choreographer, I would stretch Jean-Daniel’s metaphor to include dancers — cold, drafts, real or imagined, ABOUND when the creator is watching! 😀

June 3rd, 2011 at 10:39 am

Re: singers being nervous about mistakes in front of the composer. I think Jean-Daniel’s comment about feeling more exposed than instrumentalists is spot on, but I would add that the rehearsal culture at opera companies tends to be unforgiving. Most singers are expected to arrive at rehearsals with the music near perfection (at least technically, if not interpretively); rehearsal time is meant for stage direction. Obviously such expectations, as well as the whole rehearsal process, should be adjusted for a premiere, but new music is still a rarity for most opera singers. And that’s the other part of it: when was the last time your singers performed the music of a living composer with the composer in the room? Instrumentalists have that opportunity with much greater frequency than opera singers, who just might not be used to it.

June 4th, 2011 at 5:28 pm

Nico,

You are the wind as it moves with water. You are a tree at the top of a mountain as the sun reflects a glow. You’re choice of notes are the fodder that follows my meditative walk. As i play this cello, your melodies invade like a polite ripple in the lake. i am full, and i cannot express to you enough the sincerity i feel as you make words dance in my brain.

thank you, and be well-

June 5th, 2011 at 2:21 am

Nico,

Should you be in the UK this next month, I would be pleased to invite you to the lively coastal resort of Brighton for the purpose of speaking to members of the listening & discussion group MOOT: Music of Our Time.

Last month MOOT focused on so-called experimental minimalism. This week we’re looking at your music on minimalism from the 1980s to today – I shall include an excerpt from your ‘Seeing Is Believing’, from last night’s prog with Sara M-P.

It would be great if you could come here (it’s an hour by train from London) and talk about your music. I can guarantee you a receptive audience!

Kind regards,

Norman

PS – Looking forward very much to seeing Two Boys on July 6th.