Eerily Composed

by Rebecca Mead, The New Yorker, February 11th and 18th, 2008.

Nico Muhly, a composer, was bounding through Chinatown, his hands thrust into the pockets of a black jacket, and a too small Icelandic knitted cap pulled halfway down over his ears, heading for the market under the Manhattan Bridge. Muhly, who is twenty-six, had a violin concerto that needed writing, but he also had a pot of Bolognese sauce that needed cooking. Negotiating his neighborhood like a Parisian matron, Muhly bought ground beef from one butcher and two kinds of pork, lean and fatty, from another. He bought a head of celery and, for good measure, some ducks’ feet to use in making stock.

Muhly learned to cook as a child, and he finds the alchemy of the kitchen consonant with the composer’s art. His own kitchen is in a modestly appointed loft on the sixth floor of a building sandwiched between two storefronts on Division Street. The apartment, which Muhly shares with a roommate, Liz Gately, who has been his best friend since high school, has aged plank floors, single-glazed windows, and a gas heater mounted on a wall perilously close to a coat hook; white Christmas lights, strung along the walls, provide illumination. On one side, the loft overlooks a rooftop day-care playground. At intervals, the apartment fills with the sound of urgent, piping voices, and little heads can be seen bobbing up and down just beyond the foldout couch.

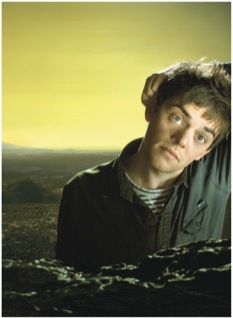

Returning home, Muhly shed his jacket and started chopping garlic. He is tall, and has the wholesome good looks of the nice one in a boy band, with wide-set eyes, a trace of freckles, and dark spiky hair that, even by day, sometimes bears a dusting of the glittery makeup that he wears to certain performances. He turned to the stove and started sautéing ground beef and onions. English choral music played on his laptop.

Returning home, Muhly shed his jacket and started chopping garlic. He is tall, and has the wholesome good looks of the nice one in a boy band, with wide-set eyes, a trace of freckles, and dark spiky hair that, even by day, sometimes bears a dusting of the glittery makeup that he wears to certain performances. He turned to the stove and started sautéing ground beef and onions. English choral music played on his laptop.

Sixteenth- and seventeenth-century English composers of religious music, in particular William Byrd and John Taverner, are among Muhly’s chief influences, though he also draws musical inspiration from the spare repetitions of Philip Glass and Steve Reich and from the off-kilter rhythms of songs by Björk, whose recordings he has worked on. “Quiet Music,” a solo for piano by Muhly and played by him on his début CD, “Speaks Volumes,” which was released a year and a half ago, has the haunting, fragmentary quality of an anthem heard from stone church steps through heavy ecclesiastical doors. Another piece on the album, “Keep in Touch,” is a duet between a swooning viola””recorded with alarming intimacy, so that the scrape of bow on string is bared like a scar””and the aching vocalizations of Antony Hegarty, the lead singer of the indie band Antony and the Johnsons. “He paints the sky with his work,” says Hegarty, who appeared with Muhly last year at the Brooklyn Academy of Music, in a concert of his own songs, which Muhly helped arrange for the Brooklyn Philharmonic. “The melody and notes are almost invisible, and he thinks in terms of these panoramas of shifting energy, which at their best are so beautiful.”

Philip Glass, for whom Muhly has worked since his sophomore year of college, at Columbia, says that he finds in Muhly “a curious ear, a restless listening, and a maker of works. He’s doing his own thing.” (Although Muhly is much in demand as a composer in his own right, he still has a day job, which includes feeding Glass’s film-music manuscripts into a computer program that can play the scores.) Following the model of Glass, Muhly prefers to have his work performed as often as possible, and in as many different contexts as possible, rather than refining his compositions within the academy. In the past year, American Ballet Theatre staged a ballet, “From Here on Out,” on which Muhly collaborated with Benjamin Millepied; the Boston Pops premièred his composition “Wish You Were Here”; and he made his Carnegie Hall début as a composer, when a program of his works, which he paired with Renaissance choral music, was performed in Zankel Hall. “In the classical world, it’s, like, bad, or too popular, to produce a lot, but you learn such a lot by listening to a piece and, literally, not being able to stop it,” Muhly told me. “It feels to me more like food, in that sense. People need to eat. You may as well make them something to eat.”

Just as, thirty years ago, Glass and his peers experimented with new modes of performance”””Einstein on the Beach” lasted five hours without intermission, during which the audience was invited to wander in and out””Muhly has an easy familiarity with contemporary media and an openness to being heard through novel means. He recorded “Speaks Volumes” with Valgeir Sigurðsson, an Icelandic musician and producer best known for his work with Björk, and released the album on Sigurðsson’s label, Bedroom Community, rather than on a traditional classical label. (Muhly’s second CD, “Mothertongue,” which he also recorded with Sigurðsson, will be released in May.) Muhly makes some of his recordings available on his Web site, Nicomuhly.com, and on his MySpace page. “People five years older than me are always deeply confused about what MySpace actually is, and people five years younger are deeply into it, but people my age are, like, “˜Yes, this is essentially where pedophiles are, and there is also music there,’ “ he says.

“I am convinced right now that anyone who is doing stuff that I just adore””I am going to wind up having access to it, whether through a commercial enterprise or through the Internet,” Muhly says. “There are people who don’t need the traditional structure of “˜I heard this concert,’ or “˜I heard it on NPR.’ “ He can be similarly ecumenical about the distribution of his own time and energy. In the past several years, thanks to his work with Sigurðsson, Muhly has spent a great deal of time in Iceland, and has become a proficient student of the language, an avid user of Reykjavík’s municipal geothermal bathing facilities, and a connoisseur of local delicacies such as puffin-meat tidbits wrapped in bacon. Last year, the members of an Icelandic rock group asked him to write them some choral arrangements””but the only recompense they could offer, they said, was to make him a mojito. Given the expense of foodstuffs in Reykjavík, where so much is imported, this was a large gesture. “The limes and mint””that must have cost them a hundred dollars,” Muhly, who was only too happy to oblige, says.

When Muhly composes, the last thing he thinks about is the actual notes that musicians will play. He begins with books and documents, YouTube videos and illuminated manuscripts. He meditates on this material, digesting its ironies and appreciating its aesthetics. Meanwhile, he devises an emotional scheme for the piece””the journey on which he intends to lead his listener. Muhly believes that some composers of new music rely too heavily on program notes to give their work a coherence that it might lack in the actual listening. “This stupid conceptual stuff where it’s, like, “˜I was really inspired by, like, Morse Code and the AIDS crisis,’ “ he says. Even so, his own work is informed by his extra-musical interests and obsessions. “Wonders,” a track on “Mothertongue,” includes the ethereal voice of Helgi Hrafn Jónsson, an Icelandic performer, singing fragments in English from “The Travels of Sir John Mandeville”; a sonnet about sea monsters, composed by King James I; and a 1619 complaint against Thomas Weelkes, the composer and organist at Chichester Cathedral, for his repeated drunkenness. “The Only Tune,” also on “Mothertongue,” is another Muhly collage””a dismantled traditional English song about a violent sororicide, delivered with affecting flatness by an American folk singer named Sam Amidon, to the accompaniment, variously, of a sampled Farfisa organ similar to that used by Philip Glass in “Music in Twelve Parts,” a pair of butcher’s knives scraping against each other, a recording of whistling Icelandic wind, and the sound of raw whale flesh slopping around a bowl.

Muhly’s violin concerto, which was commissioned by the Aurora Orchestra””a new, young British ensemble that specializes in modern music””and was to be performed at the Royal Academy of Music, in London, is based largely on Renaissance astronomy, though it also has roots in educational videos about the solar system of the sort shown in schools in the nineteeneighties. (One day, Muhly e-mailed me a link to a YouTube video featuring the resonant voice of Carl Sagan giving a tour of the constellations.) For this piece, Muhly had been contemplating, among other documents, a diagram of the universe dating from 1576 and taken from a book by Thomas Digges, an English proponent of the theories of Copernicus: it showed a series of concentric circles, the innermost one representing the sun and the outer one representing “the pallace of foelicitye garnished with perpetuall shininge glorious lightes innumerable.” Another inspiration was an engraving from a treatise about sunspots by the Jesuit astronomer Christoph Scheiner. The pathos of the Renaissance astronomer’s situation appeals to Muhly, and speaks to the composer’s task of creating emotional resonance through the mathematical arrangement of notes. “In the Renaissance, everyone was trying to negotiate a relationship with the divine,” he explains. “And there is an inherent emotional content to scientific studies, even though science is supposed to be divorced from that.”

Muhly has an associative intelligence that is facilitated by Google and iTunes. The image from Digges reminded him of an anthem by William Harris that sets part of a poem by Edmund Spenser (“Fair is the heaven where happy souls have place / In full enjoyment of felicity”), and that prompted him to listen again to a recording of Elizabethan minstrel songs by the countertenor Alfred Deller. Looking at a series of images of the sun marked by sunspots””which reminded him of a computer screen cluttered with icons””he thought of a passage from Roland Barthes’s “The Empire of Signs,” in which Barthes says that a chopstick “introduces into the use of food not an order but a caprice, a certain indolence.” Muhly decided that “a certain indolence” might be a good characterization of the mood with which he wanted his violin concerto to conclude.

Muhly usually composes on sheets of manuscript paper, though sometimes he also uses an electronic keyboard, which sits on his desk next to two large computer monitors. One afternoon when I was watching him at work, one screen displayed two pages of a score, and the other showed his e-mail inbox and several open instant-message chats with friends. (Muhly does not require silence or seclusion while working and, in addition to conducting multiple online conversations while composing, often has several online games of Scrabble under way.) The section of the concerto that he was working on was inspired, in part, by another image: a stage design by Karl Friedrich Schinkel for an 1816 production of “The Magic Flute,” in which the realm of the Queen of the Night was represented by a midnight-blue dome studded with stars spaced at regular intervals, like the inside of an inverted colander.

Muhly’s concerto, which was for an electric violin accompanied by a chamber orchestra, was to be a nocturne of sorts. “Mozart is so good at pre-Romantic notions of the night,” he says. “We all know Mahler, but with Mozart you get this kind of evening-y thing, with an awareness of light and space.” Muhly had also been thinking about Mozartian articulation for his concerto: “There is the possibility, in Mozart’s music, that there are all these little moving parts that you can make a very big deal out of, if you want to.” Although Muhly’s composition would sound nothing like Mozart, it was to have its own little moving parts: a series of eleven chords that would eventually be sorted into a harmonious whole””much as Christoph Scheiner and Thomas Digges, in their observations of the night skies, fashioned godly order from apparent chaos.

A message from a friend popped up on Muhly’s second screen, asking him if he had read an essay by Bernard Holland in the Times about the impact of first hearing “Einstein on the Beach.” Holland had written a curmudgeonly review of Muhly’s Carnegie Hall concert, declaring himself unable to see the connection between the older works and the newer. (“He reviewed the show as if I were having a dinner party and he’d showed up in the middle of it,” Muhly told me.)

” “˜Einstein'””changing old people’s lives since 1976,” Muhly typed back, and turned again to his music.

n early November, about two months before the violin concerto was to be performed, Muhly flew to London to meet with Thomas Gould, the soloist, and Nicholas Collon, Aurora’s director and conductor. The meeting took place at Gould’s flat, on the creaking top floor of a dilapidated mansion not far from Regent’s Park. Gould, who is twenty-four, and who had floppy light-brown hair and an unshaven chin, sat on a sea-green Naugahyde couch that had been draped with a raw-cotton sheet, the electric violin on his lap plugged into an amplifier by his feet. Collon, who is also twenty-four, sat on the floor in jeans and a baggy knitted sweater, a blue sock on one foot and a gray one on the other. The floorboards sagged under a grubby carpet that, when Muhly walked across the room, gave slightly underfoot, like the barely cooked crust of a pudding.

“I have some notes for you,” Muhly said excitedly, pulling a few pages of music manuscript from his leather satchel and handing them to Gould, who was playing with the controls of his electric violin. When Gould pressed a foot pedal, a tinny, Casio-style drumbeat started up. “I haven’t played it for a while,” Gould said apologetically, hurrying to quash the sound.

“Does it have a bossa-nova beat?” Muhly joked.

Once the machine had been tamed, Muhly asked Gould to experiment with some different techniques: grating the bow to snarl the grace notes at the beginning of phrases; bouncing the bow across the strings to create an aural ricochet; pressing the foot pedal after each phrase to build up layers of sound, one upon another.

“Now I want it slower, and super Brahmsy,” Muhly said, and Gould drew the bow slowly over the strings, until the room was filled with the violin’s keening.

“It’s so eighties!” Muhly said. “Like David Bowie!”

“All we need now is a crystal disco ball,” Collon said, with pleasure.

Muhly’s personal experience of the eighties involved more sandboxes than discos: he was born in 1981, to Bunny Harvey, an artist, and Frank Muhly, a filmmaker. Nico was an only child. “One was the absolute border of how many kids my parents were going to have,” he says. It was an unconventional childhood: the Muhlys split their time between an eighteenth-century farmhouse in the tiny town of Tunbridge, Vermont, and a house in Providence, Rhode Island, convenient for a teaching job that Harvey secured at Wellesley. His parents’ work sometimes took the family overseas: when Nico was seven, they spent several weeks living near an archeological site outside Luxor, in Egypt. (Nico’s strongest recollection is of being chased by a pack of wild dogs.) In Vermont, they grew their own produce and slaughtered their own sheep, at the end of the yard. “My mother is the only person anyone knows who will eat all the nasty stuff,” Muhly says. “When the neighbors kill a deer, they call and tell her where they did the field dressing, and she goes in the middle of the night and grabs the heart.”

Muhly says that he learned early that his mother’s commitment to her work was inviolate, and that her experience of motherhood was not without ambivalence. “Sometimes she would look at me and be mystified by the object of me,” he says. When Muhly was about three, Harvey painted his portrait; in it, he stands, blond and serious-looking, in a field, peering through tall grasses, next to the ghostly outline of an erased maternal figure. The painting is called “Evil Nico.”

Muhly has a fond, if still somewhat fraught, relationship with his mother, who, along with his father, attended a celebratory dinner for about forty of Muhly’s friends at the Fuleen Seafood Restaurant, in Chinatown, after a performance of Muhly’s ballet at American Ballet Theatre. Muhly went from table to table, showing off a congratulatory gift from his mother: a life-size, lifelike model of a crow, paired with a candle in the shape of a pinecone. “She said you can light the candle and have the crow look at it, or you can light the candle under the crow,” he explained with glee.

“You know how crows and magpies and blue jays are the juvenile delinquents of the air? I see Nico pulling things out of the air,” Harvey told me later, explaining the gift. “I wouldn’t say Nico is a thief, but he is greedy for information and possibility.” Harvey recalls that, as an infant, Muhly imitated birdsong and animal sounds. She says, “When he was a toddler, I would read to him in bed, and he would be poking my leg with his finger and saying, “˜Fast forward, please,’ as if I were some mechanical device that could be encouraged to get to the point.” (Muhly retains a similar habit, when listening to music, of rapping a finger in time upon the shoulder, arm, or leg of whoever happens to be sitting or standing closest to him.)

When he was eight years old, Muhly began to learn the piano, on an old upright in the basement of the Rhode Island house, but it was not until a friend at school invited him to join a church choir that his musical affinities truly began to emerge. “My mother was horrified: she would come and hear us sing, but grudgingly,” Muhly says. (His mother is half Jewish, and his father comes from a Lutheran family; both are more likely to celebrate the solstice than any Judeo-Christian religious observance.) Muhly, however, loved the repertory of Byrd, Weelkes, and Orlando Gibbons. “I found myself immediately at home in it musically,” he says. “I was really entranced by early music, and how the lines worked. It felt so much more emotional than the Romantic stuff I was playing as a pianist””Chopin, or Schumann, or Tchaikovsky, which always felt sort of Hallmarky.”

Muhly started to play the organ in addition to the piano; one day when he was ten, his mother took him to Trinity Church, in Boston, where she knew the assistant organist. Harvey recalls, “He introduced Nico to the music director, who tried to play for him a medley of music from “˜Fantasia,’ and Nico rolled his eyes. Then the music director asked if he would like to play something. He sat down and his feet couldn’t even reach the pedals. He said, “˜I am going to play some Bach,’ and this big sound came roaring out of the organ. There were all these people taking a tour of the church who were saying, “˜Who’s playing?,’ because he was only four feet tall.” That afternoon, Harvey recalls, Muhly started composing his first piece of music, a setting of a Kyrie for choir, on a napkin at a coffee shop in Harvard Square. “He wrote it vertically””all the parts simultaneously,” she says. “He was thinking in chords, rather than in individual lines. He said, “˜That’s how I hear it.’ “ Frank Muhly says, “It was like birdsong that’s innate””something triggers it and it comes out full blown.”

Muhly says that, even as a boy, he was fascinated by the emotional function of church music as opposed to that of concert music. “Church music is more directional music, pointing upward,” he says. “And the satisfaction of a job well done is the only one you are going to get. When you finish the piece, you don’t look at the audience and smile; you don’t graciously bow. And the composer vanishes, too, in addition to the performers. If you are really good, you disappear.”

Muhly did not exactly vanish as a choirboy, his choirmaster, Mark Johnson, recalls. “He was somewhat irreverent toward the religious aspects of our work,” Johnson says. “He put out a publication for the choir called “˜The Society of the Twisted Cross’ that would twist around some of the texts we were singing, and would sometimes be very descriptive of members of the choir.” Muhly assisted Johnson by doing computer transcriptions of the singers’ parts, to which he made his own emendations. “He was very anti-God at the time, and he would always lower-case the “˜g,’ like e. e. cummings,” Johnson says.

Since moving to New York, seven years ago, Muhly has regularly attended St. Thomas Church, on Fifth Avenue at Fifty-third Street. In 2005, he composed a “Bright Mass with Canons” for its choir. “The organ writing is very colorful and very brilliant, and what is so attractive to me is that he is using ancient techniques,” John Scott, the director of music at St. Thomas, says. “Canon, where voices imitate each other and sing the same music but not at the same time, came to its fruition among early-sixteenth-century Flemish composers. Nico Muhly is in a sense coming from there, but it is dressed up in a very contemporary musical language that has aspects of minimalism.”

Muhly’s youthful anti-clericalism has been tempered by time: though Scott told me that he and Muhly have never discussed questions of faith, he added, “I suspect that he is quite serious about it.” Muhly told me, “I am quite serious about church music. Musicians have always enjoyed a “˜question-free zone’ about faith, because religious music can help people explore their relationship with the divine, which I think is a much more powerful altruistic act than making a big scene of your own personal relationship. I started going to St. Thomas here, and it wasn’t even a question for a second that I wanted to live a life that includes liturgical music as a major part.”

Muhly’s command of the English religious-music tradition informs his non-liturgical compositions, too, if sometimes rather impishly. When I joined him one day at his office at Philip Glass’s studio””he works in a soundproofed interior room surrounded by high-end digital equipment, a few packages of dried seafood from Chinatown tacked to a corkboard for color””he was working on a section of his violin concerto, writing parts for the marimba, the strings, and the piano. “Now, if you want to make it really godlike, here’s what you do,” he said, and keyed in a few throbbing bass notes. “There is a specific way the bass works that makes the English go crazy,” he explained. “It’s like catnip for them, so I try to take advantage of it. I love a good nineteenth-century national stereotype. It is really useful in composition.”

When pressed, Muhly describes himself as “a nonbeliever, but with cheating.” He says, “I feel an enormous attraction to the liturgy, to the tradition. On a certain level, going through rituals and living a year with an awareness of a liturgical calendar, as I have at St. Thomas, is really, really amazing””mapping out a year with respect to that is a super-interesting thing to do. For me, it is culturally bizarre that it should happen to be High Anglicanism. But that is where the music is.”

hen Muhly was thirteen, his mother was a visiting artist at the American Academy in Rome for six months, and he went along with her. The experience, he says, was life-changing: “I wanted desperately to go to the British boarding school with the uniforms, but my mother was, like, uh-uh, so I went to Italian public school, which was such a zoo, with every chaotic stereotype you can imagine: it was in this Fascist building, and everyone was fighting each other all the time.” (Bunny Harvey, who points out her son’s propensity for narrative embroidery, insists that it was actually Muhly’s idea to attend public school.) “I was mad at my mother for so long, and then my Italian got really good really fast, and I stopped hating my mother, and the possibility of joy reëntered my life.”

At the academy, there was an unused studio equipped with a piano; Muhly was allowed to take over the space. “The community at the academy took him seriously,” Harvey says. “People loved talking to him, and he realized that there wasn’t such a difference between being an intelligent kid and being a fully fledged creative person.” Among the people he made friends with were Maira Kalman, the illustrator and author, and the late Tibor Kalman, the graphic designer. “I had met Bunny and had heard her talking about her son, but without really paying attention,” Maira Kalman says. “Then Tibor and I walked past his studio and heard him playing, and it was extraordinary.” (Two years ago, Muhly collaborated with Kalman on a whimsical operatic interpretation of “The Elements of Style,” the language-usage manual, which was performed in the Rose Main Reading Room, at the New York Public Library.) In Rome, Muhly developed an obsession with the bus system, and would ride the buses for hours after school, exploring the city. “In the period of time when my language was really good, when I had Italian friends, when I had my bus pass, I was, like, if this is what life can be like, given certain conditions, let’s aim for this in the future,” Muhly says.

He attended high school in Providence. Kenneth Clauser, his high-school adviser, first came across him when a French teacher reported that one of her sixth graders would be missing a class because he had to play the organ for a wedding. He recalls that Muhly led a group known to the teachers as the Grammar Patrol: “They would patrol the campus and correct the grammar on the signage. He was a stickler about expression.” Muhly also took a leading role in directing the music for theatrical productions, including “Fiddler on the Roof” and “Bye Bye Birdie,” into which he inserted sections of Stravinsky’s “Petrushka” and “The Firebird,” and selections from Abba.

In his final years of high school, Muhly studied composition with David Rakowski, a professor at Brandeis, and he worked his way obsessively through the contents of Wellesley’s music library, absorbing the works of Steve Reich and other minimalists. “I got hold of Reich’s “˜Music for Eighteen Musicians’ somehow, and I had an immediate visceral and emotional reaction to the repetition and pattern-making,” he says. “It sounded so much like how my head worked.” At fourteen, he attended a summer program at Tanglewood. The fashion designer Isaac Mizrahi, whom Muhly had met through the Kalmans, held a musicale in his New York apartment to raise money for Muhly to go to Tanglewood; one of the guests was the choreographer Mark Morris. (Muhly has a gift for acquaintance: “More people have met me than have heard what I do, and I am working to change that,” he says.) Mizrahi recalls, “Nico played Stravinsky’s piano version of “˜Petrushka,’ and jaws dropped. Then he said, “˜I am going to play one of my own compositions. I don’t usually do this kind of thing, because I’m not a trained monkey, so I’m going to do this once, and you had better listen.’ “

At eighteen, Muhly enrolled in a joint program at Columbia, where he studied English, and Juilliard, where he got a master’s in composition. Columbia’s core curriculum includes a music-appreciation course, which students can test out of. On the afternoon the test was held, Muhly, who by then had begun working part-time for Philip Glass, was due to fly to London to work on Glass’s film score for “The Hours.” “It was a two-hour test, and there was an hour of listening and an hour of multiple choice,” Muhly recalls. “I thought, The only way I can do this is if I can get out in an hour and ten minutes, so I will have to do the listening as fast as I can and hope for the best. In the listening part, you had to write down as much as you could about what you had heard, so you could write, “˜Oh, it sounds like Baroque music.’ But you could also write, “˜That’s Bach’s Third French Suite, it’s Glenn Gould’s recording, God damn it, can I please go to England now?’ “ Muhly passed the test and made his flight.

At Columbia, Muhly shared a sprawling faculty apartment with an astrophysics student named Will Serber, whose late father, Robert Serber, was a physics professor who had worked on the Manhattan Project. “I get the impression he lived there partly because it was a good story,” Serber, who remains Muhly’s close friend, told me. “I remember at some point he owed me twenty dollars, and he returned it to me all in singles in inconvenient places. I would go and take a shower, and a dollar bill would emerge from my shampoo bottle.” Muhly took Edward Said’s course on the history of the novel, and studied Arabic. At Juilliard, where he was studying with the composers Christopher Rouse and John Corigliano, Muhly was unusually productive. “He would bring in thirty or forty pages of music a week, and if twenty-five of them didn’t work out he would have no problem with that,” Corigliano says. “We worked on structure, but the skill of writing virtuosically for winds, brass, percussion, strings””he came in the door with that.” Muhly formed alliances with a number of musicians who have become regular collaborators, including Nadia Sirota, a violist. Sirota says of Muhly, “He is different from a lot of composers his age in that he prefers a kind of old-school way of approaching string playing, from the style of the forties and fifties, with lots of vibrato, and very romantic.”

Philip Glass told me, “The great anxiety among young composers is, when are you going to hear your own voice? But the real problem is, how do you get rid of it, how do you develop? Nico hasn’t got to that yet. There is a lot of rapid growth in one’s twenties, but the big challenge is to keep that alive over the long stretch, for the next forty years, and not let it get stifled by the meanness of the world we live in.” John Adams, who curated the Zankel Hall series in which Muhly’s work appeared last year, says that Muhly’s music is “eclectic, nondenominational in the world of contemporary classical music, which tends to split off into lots of different orthodoxies. He obviously shows influences from the minimalist composers, but his music is not nearly as rigorously designed. It is very much like him: it is open, it is attractive, it is pleasing.” Adams says that he hears his own influence on Muhly’s work”””It’s like meeting a twenty-year-old who looks strangely familiar, only to discover he’s your long-lost son”””but adds that he finds it oddly untroubled. “I could use a little more edge, or a little more violence,” Adams says. “At times, there is a surfeit of prettiness in Nico’s music, and I am not sure it is a good thing for someone so young to be so concerned with attractiveness.”

“That is a criticism I have of myself all the time, too,” Muhly told me. “Why does everything have to be so beautiful all the time? It’s like going into someone’s apartment and asking, “˜Why does everything have to be a beautiful object? You people suck.’ “ Muhly points out that “Mothertongue,” the new recording, is much less sweet, filled with jittery, anxious repetitions and jarring chords that are intended to suggest the nauseating atmosphere of international jet lag and airport stultification, along with more mundane domestic anxieties. For the title track, Muhly layered the voice of Abigail Fischer, a mezzo-soprano, singing all the addresses at which she has ever lived on top of recordings of another friend taking a shower, eating toast, and frying an egg.

The prettiness of Muhly’s music is, in any case, not unconsidered. “There is a way to get away with writing music these days that is like making big, abstract paintings without ever learning to draw a piece of fruit or a landscape,” he says. “There exists a lingua franca of classical music that is just indiscriminately ugly. And so when I was in school I set out to get involved in learning how to write beautiful textures, just to see what that was like, because no one would ever tell you how to really space out a chord. So all the stuff on “˜Speaks Volumes’ is very pretty on purpose, just to say you can do this and still have it be meaningful and have emotional content. If there is an emotional depth to my stuff, it is always from a weird place of repetitions lulling you into a sense of security and then taking it away, so it’s a perversion of what you expect; or something being so pretty and so saccharine that you wonder if it’s witch’s candy.” One such unsettling moment occurs in “It Goes Without Saying,” the second track on “Speaks Volumes,” when the sound of woody, beeping clarinets is gradually overcome by threatening digital noise.

Muhly politely cavils at Adams’s suggestion that youth should indicate anger. “When one’s twenties were spent in 1968″”yes, you probably were pretty angry about things,” he says, referring, in part, to the fierce partisanship that characterized the New York classical-music scene at the time, with academicians and critics advocating a rigorous complexity while an oppositional aesthetic, minimalism, was emerging downtown. “But I think in my twenties I am just more hyperaware and hypersensitive,” Muhly says. “If I am going to talk about angry, I will do it in a really reserved way. I will do it like in the Passions, where you get the crowd saying, “˜Crucify him,’ and it is always so gorgeous. I don’t have it in me to write music about an emotion I don’t innately have.”

Obsession, anxiety, and loneliness are, however, omnipresent in Muhly’s work, even when his music seems, on the surface, most eager to please. “Wish You Were Here,” which Muhly composed for the Boston Pops, is expressive and romantic, an orchestral impression of the exotic strains of traditional Balinese gamelan music. Muhly’s invocation of the gamelan calls to mind Benjamin Britten, who incorporated gamelan music into “Death in Venice” and other works after travelling to Bali and being inspired by the beauty of the music, and by the beauty of the youthful musicians playing it. “If I am speaking to other composers, Britten is one,” Muhly says. “I’m saying, “˜You can have this, and it doesn’t have to be a secret, shameful thing””this influence, this exoticism.’ “ Britten is a significant figure in Muhly’s musical””and social””imagination. “Britten’s music is important to Nico, but I think Britten’s loneliness is, too,” Dan Johnson, a music critic and blogger who is a friend of Muhly’s, and who often writes his program notes, says. “Although, from my point of view, Nico seems to be right at the center of things, I think he still feels somehow isolated and out of place. His music can be terrifically glossy. But the gloss always has these tiny cracks in it, and sometimes the places where these cracks open up are the most important part of the piece.” Neal Goren, the artistic director of Gotham Chamber Opera, which plans to commission a work from Muhly, says, “Nico is not one of those composers who writes music to hide who he is.”

The shade of Britten also inhabits one of Muhly’s more ambitious forthcoming projects: an opera to be co-commissioned by the Metropolitan Opera and Lincoln Center Theatre. (Negotiations are still under way, but Peter Gelb, the general manager of the Met, says, “He’s the type of composer that we in the opera world, and in the classical world, are always looking for””someone who is both original and accessible, and who has the potential to be instantly appealing.”) Muhly’s proposed plot, which has the dark ambiguity of “Peter Grimes,” is based on a lurid British true-crime story involving a fourteen-year-old boy who, through a complex series of Internet chat-room impersonations and ruses, fulfilled an erotic fantasy by luring another boy to meet him in an alleyway and stab him.

“To me, what he did was he composed something,” Muhly says of his projected protagonist. “He wrote this thing, completely scripted, that happened to his own body. You see a dancer walking around and you are, like, dancer, because he is all turned out. And when you see a violist you are, like, violist, because he has this thing on his neck. And with composers, there is a secret, late-night knife to the chest.”

he Aurora Orchestra gathered to rehearse Muhly’s concerto at St. Mary’s Church in Barnes, in southwest London, a few days before the performance, in early January. As the musicians warmed up, Muhly wandered around the church, admiring the change bells in the bell tower and peeking into the vestry, which had shelves stacked with candles and racks of clerical gowns. At one point, the orchestra ran through another piece on the program: two motets by William Byrd, arranged by Muhly. A puzzled clarinetist said that a note he had been assigned sounded wrong, and Muhly explained that the bum note was deliberate: his composition was not merely an arrangement of Byrd’s score but, rather, an imitation of a live, imperfect performance of the music. When the orchestra turned to Muhly’s own composition, the musicians””a trombonist in a stocking cap, a double-bass player in a Led Zeppelin T-shirt””cast serious glances in Muhly’s direction as they set to work on the score. Muhly sat back in his seat with satisfaction. “This is just what I wanted,” he said after a few minutes. “It’s busy, but clear. Like bees. Organic.”

At the Royal Academy of Music, a few nights later, Muhly, dressed in a dark jacket and pants and a black sweater over a white shirt and a sparkly silver tie, sat toward the rear of the concert hall. Looming portraits of academy alumni hung on the walls, and four enormous chandeliers were suspended above. The piece began with the melancholy song of the electric violin””looped, three-note phrases overlapping, but never precisely matching up, to create disordered sonic patterns, like uncharted stars. Gradually, other instruments joined in, strings and woodwinds picking up the violin’s three-note signature to form clear constellations of sound. As the momentum built, the entire orchestra was shaped into harmony by the resonant, otherworldly violin. Toward the concerto’s conclusion, the violin engaged in a duet with the celesta””an instrument named for its heavenly sound, and much favored by Muhly””while the other instruments faded out, as if vanishing into a lightening sky.

Muhly had entitled the piece “Seeing Is Believing,” a punning reference to the problem of reconciling faith with science faced by the sixteenth-century astronomers whose studies had provided the score’s original inspiration. However, the program notes, which Muhly had written, made no mention of the Renaissance. “At a certain point, all that falls away,” he said, standing in the lobby of the academy after the performance. “What was I going to write: Tycho Brahe, blah, blah, blah? Can you imagine? It’s too much information. In the end, it’s just “˜Look at the stars, here’s some music.’ “

By the time Muhly reached the reception that was being held in a basement concert room, he was already thinking about his next project: a collaboration with a singer from the Faroe Islands named Teitur Lassen, to be performed by the Holland Baroque Society in three Dutch cities in March. Lassen had come to London to hear the concerto, and he and Muhly huddled in a corner laying plans for their new piece, which was to consist of music composed to accompany a series of YouTube videos that had been chosen expressly for their mundanity.

“There’s a way to search for interesting things on YouTube, and then there’s a way to search for uninteresting things,” Muhly said. “You put in search terms like “˜My daughter’s yard,’ “˜My friend’s restaurant.’ “ The music was to be modelled on cantatas by Bach and anthems by Purcell, he explained. It was going to be great.

2 Comments

February 9th, 2008 at 11:52 am

The New Yorker article really stimulated my interest, and now listening to the Violin Concerto on this website has made me a fan, so I’ve ordered the recording. I’m looking forward to getting much better acquainted with Nico Muhly’s music!

February 9th, 2008 at 7:49 pm

I am writing in regard to the criticism by John Adams, “…I am not sure it is a good thing for someone so young to be so concerned with attractiveness.” As long as the work (in any art) that is created is arrived at honestly, the natural by-product is beauty. (Truth is beauty…and so on). Something like beauty can be achieved formulaically, but can be detected by its saccharine aftertaste. I have never heard any of your pieces, but from one artist to another, please do not doubt the “attractiveness” of your work if it was arrived at honestly. Really, it’s just postmodernism talking.