Faroe (Part III): Native Tongue

from Sunday, July22nd of the year2007.

Over the last few years, I’ve worked with a number of excellent singer-songwriters, gone to a million shows, festivals, whatever. I’ve been thinking a lot about what it  means to sing in English rather than one’s own native tongue; I think it sort of goes without saying that a lot of foreign pop music happens in English because there is a sense that English is understood by most people, and that your music can be better appreciated if people understand the lyrics. Fair enough. However, there is a lot of wonderful music not in English that American or other English-speaking audiences can appreciate: I’m thinking about Edith Piaf, or Sigur Rós, or Oum Kalthoum, or Camille, or really anybody: the list is endless. And then there are people like Björk, who could sell anything in any language; there are other people in that category who are native English speakers so it doesn’t really come up, but you had better believe that if Prince sang in German or Thai or Quechua you would take your panties off and throw them promptly at the stage. I suppose we take it for granted in the Classical tradition that the majority of sung music will be in German, French, or Italian, just given the enormous history of song and opera in those languages.

means to sing in English rather than one’s own native tongue; I think it sort of goes without saying that a lot of foreign pop music happens in English because there is a sense that English is understood by most people, and that your music can be better appreciated if people understand the lyrics. Fair enough. However, there is a lot of wonderful music not in English that American or other English-speaking audiences can appreciate: I’m thinking about Edith Piaf, or Sigur Rós, or Oum Kalthoum, or Camille, or really anybody: the list is endless. And then there are people like Björk, who could sell anything in any language; there are other people in that category who are native English speakers so it doesn’t really come up, but you had better believe that if Prince sang in German or Thai or Quechua you would take your panties off and throw them promptly at the stage. I suppose we take it for granted in the Classical tradition that the majority of sung music will be in German, French, or Italian, just given the enormous history of song and opera in those languages.

In Iceland, the tradition seems to be that if you want your music to be Internationally Recognized, for better or for worse, it should be in English. This is easily enough done, because most Icelanders speak English the same way people in India do: a complete fluency with a distinctive accent. So, to write lyrics in English isn’t a mental strain or pretentious or anything.  The question, though, is what it means to write music in a language that is not your mother tongue, no matter how fluent in it you might be. The sound of a native speaker is inimitable and intimate, particularly in Icelandic, a language with an assortment of phonic intricacies. Global English, on the other hand, is composed of many different Englishes, and I feel like some of the tighter details of it get lost in song. There are a few very popular English-speaking singers-songwriter whose native accent shines through; I’m thinking in particular of the Winston-Salem twang that peeks through Ben Folds’s songs, or Owen Pallett/Final Fantasy‘s shielded Canadian vowels.

The question, though, is what it means to write music in a language that is not your mother tongue, no matter how fluent in it you might be. The sound of a native speaker is inimitable and intimate, particularly in Icelandic, a language with an assortment of phonic intricacies. Global English, on the other hand, is composed of many different Englishes, and I feel like some of the tighter details of it get lost in song. There are a few very popular English-speaking singers-songwriter whose native accent shines through; I’m thinking in particular of the Winston-Salem twang that peeks through Ben Folds’s songs, or Owen Pallett/Final Fantasy‘s shielded Canadian vowels.

This weekend, I went to a show by Pétur Ben, an lovely Icelandic singer-songwriter, whose album Wine for my Weakness is entirely in English. His English is, of course, perfection, but why was it that the one song he sang in Icelandic felt, to me, more nuanced?  His way around the rhymes and his navigation of Icelandic’s boulder-like consonants feels like driving on a country road with somebody who truly could drive it with their eyes closed; in English, it has the feeling of British people who have lived 35 years in Tuscany, whipping around hairpin turns and occasionally clipping a neighbor’s mailbox.

His way around the rhymes and his navigation of Icelandic’s boulder-like consonants feels like driving on a country road with somebody who truly could drive it with their eyes closed; in English, it has the feeling of British people who have lived 35 years in Tuscany, whipping around hairpin turns and occasionally clipping a neighbor’s mailbox.

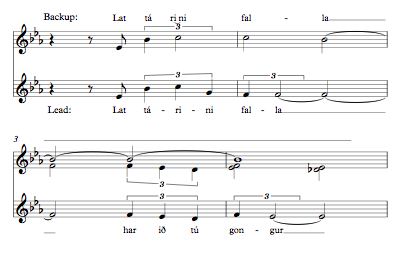

Teitur‘s show (more on him and the show in a later post), on the other hand, comprised about seven songs from his Faroese album Káta Hornið, and then three from his English-language albums. This proportion, to me, feels about right: home and away in the proper balance. His Faroese material allowed him to be more experimental with the arrangements, too, letting the language be the engine behind the music. Lat Tárini Falla, the first song off of the album, is a two-minute long affair with some of the best registral articulation in pop music I have heard. Listen to how the backup voices make a halo around the sound, and how the lead vocal, guitar, and halo have three different rhythmic footprints. Additionally, you can hear in the first three words a geological intricacy of Faroese (the double-L trick which exists in a slightly more severe form in Icelandic). You couldn’t get a fraction of this if this song were in English.

Teitur‘s show (more on him and the show in a later post), on the other hand, comprised about seven songs from his Faroese album Káta Hornið, and then three from his English-language albums. This proportion, to me, feels about right: home and away in the proper balance. His Faroese material allowed him to be more experimental with the arrangements, too, letting the language be the engine behind the music. Lat Tárini Falla, the first song off of the album, is a two-minute long affair with some of the best registral articulation in pop music I have heard. Listen to how the backup voices make a halo around the sound, and how the lead vocal, guitar, and halo have three different rhythmic footprints. Additionally, you can hear in the first three words a geological intricacy of Faroese (the double-L trick which exists in a slightly more severe form in Icelandic). You couldn’t get a fraction of this if this song were in English.

[audio:TeiturLatTarini.mp3]

Teitur Lat Tárini Falla from Káta Hornið

This sketch, below, is a rough example of the “rhythmic footprint” thing ““ the voices are basically doing the same thing as the lead vocal, just slightly slower. They hold onto  notes suggested by the lead vocal, creating a beautifully liquid, out-of focus, cartoon-drunkenness, or, as the lyrics of the song would suggest, the experience of seeing through tears (“Let your tears fall wherever you go” is my sloppy translation. I think it might be more precisely, “wherever you walk;” it could be a poetic verb or it could just be how they roll in Faroese).

notes suggested by the lead vocal, creating a beautifully liquid, out-of focus, cartoon-drunkenness, or, as the lyrics of the song would suggest, the experience of seeing through tears (“Let your tears fall wherever you go” is my sloppy translation. I think it might be more precisely, “wherever you walk;” it could be a poetic verb or it could just be how they roll in Faroese).

English is an awkward-ass language to set, too. The words that one uses the most often, like I, you, and me, are impossible to set in the extremes of the voice. Try singing the word “you” as high as you can and you’ll see what I mean.

English is an awkward-ass language to set, too. The words that one uses the most often, like I, you, and me, are impossible to set in the extremes of the voice. Try singing the word “you” as high as you can and you’ll see what I mean.

I also want to look at a great efficient use of Icelandic that couldn’t work out in English. This is from the Sigur Rós song Hoppípolla; the lyrics in question read, “Og ég fá blóðnasir / en ég stend alltaf upp” (“And I get a nosebleed / but I always stand up”).

[audio:SRHoppi.mp3]

Sigur Rós Hoppípolla from Takk…

The thing in question happens about 2:10 in just after a little diminuendo in the bell-like texture. Listen to the enchainement (a.k.a. External Sandhi) between alltaf and upp; the tension in the double-l [tl] consonant, followed by the f expanding into a full [v], and immediately we are plunged into a nonsense language native to the band. I like this idea that after injury and recollection comes internal language. Another place this turns up is in the second and sixth movements of Steve Reich’s The Desert Music, whose text, by William Carlos Williams, reads:

from

The Orchestra

Well, shall we

think or listen? Is there a sound addressed

not wholly to the ear?

We half close

our eyes. We do not

hear it through our eyes.

It is not

a flute note either, it is the relation

of a flute note

to a drum. I am wide

awake. The mind

is listening.

and then, as if “listening” were a pickup, the downbeat arrives with the choir singing an initially shattered and then steady rhythm on “di di di di di di” ““ the pulse language central to Reich’s emotional liturgy.

[audio:10 The Desert Music IV (Moderate).mp3]

Steve Reich The Desert Music

Alarm Will Sound, Alan Pierson, conductor

I am incredibly excited by this sort of textplay with nonsense syllables; in a sense, the central eros of the music I like the best (and the music I write) is the act of deciphering and decoding a language ““ teasing out the known syllables from babble. At a certain point, a palsy takes over, and you find yourself obsessing over a single phoneme: the dashed lines in the center of the highway, or the steady chopping of a blade.

If you like this Hot Hot Reich, please download my homegirl Alan Pierson’s recording of The Desert Music. It also has a recording of Tehillim on it, which is a majorly important work; you can read my program notes about it for a live performance here. I had originally intended on titling those notes “Pulsing before G-D,” but then the people said that they weren’t titling them (probably just to prevent me from getting, you know, GLAAD and the ADL up in their grill). As always, you can scroll down or click on the links for parts II and I of my Faroese Posts. Also, if you want to have a whole Web Adventure, you can try to buy Teitur’s Faroese Album here; it costs 112 Danish Kronur, which translates to about twenty bucks.

3 Comments

July 22nd, 2007 at 10:31 pm

Thanks, Nico! How fascinating. I already loved the Desert Music and am now excited to discover Sigur Ros and Teitur. I already have some music from the Faroe Islands- Villu Veski and Tiit Kalluste (sort of jazz/folk/with minimalist elements) and I also love Gjallarhorn from Finland, amongst others.

Loved the sunrise photos too. There’s a magic about these Nordic places…

July 23rd, 2007 at 12:23 am

I wonder if it’s only the aural qualities of a language that make song-writing in what isn’t your mother tongue so very difficult. With rare exceptions even the most fluent non-native speaker – even a speaker raised as bi- or multi-lingual – doesn’t navigate each language in quite the same way, with quite the same facility. I think it takes a particularly gifted writer like Nabokov to accomplish this. If you try to translate poetry, you will find that of course the music of the language – rhythm, cadence, types of consonants etc. etc. – is almost impossible to reproduce, but the nuances of meaning and association as well.

July 27th, 2007 at 10:33 am

Let my people go.